The pursuit of knowledge is an endless path, and we work hard to pave a road.

Ultimately, our goal is to increase the speed of human knowledge dissemination,

and equity on knowledge acquisition.

Fun with Feedback

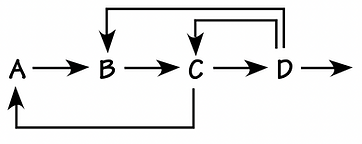

To hone our systems thinking perspective, let’s look again at feedback. As we saw earlier, feedback is the transmission and return of information. The key word here is return—it is this very characteristic that makes the feedback perspective different from the more common perspective: the linear causeand-effect way of viewing the world. The linear view sees the world as a series of unidirectional cause-and-effect relationships: A causes B causes C causes D, etc.

The feedback loop perspective, on the other hand, sees the world as an interconnected set of circular relationships, where something affects something else and is in turn affected by it: A causes B causes C causes A, etc.

As trivial as this distinction between these two views may seem, it has profound implications for the way we see the world and for how we manage our daily lives. When we take the linear view, we tend to see the world as a series of events that flow one after the other. For example, if sales go down (event A), I take action by launching a promotions campaign (event B). I then see orders increase (event C), sales rise (event D), and backlogs increase (event E). Then I notice sales decreasing again (event F), to which I respond with another promotional campaign (event G) . . . and so on. Through the “lens” of this linear perspective, I see the world as a series of events that trigger other events. Even though events B and G are repeating events, I see them as separate and unrelated.

From a feedback loop perspective (see “Thinking in Loops” on p. 6), I would be continually asking myself “How do the consequences of my actions feed back to affect the system?” So, when I see sales go down (event A), I launch a promotions campaign (event B). I see orders increase (event C) and sales rise (change in event A). But I also notice that backlogs increase (event D) (another eventual effect of event B), which affects orders and sales (change in events C and A), which leads me to repeat my original action (event B).

After looking at both the linear and feedback representations, you might be saying to yourself, “So what? I’m too busy to draw pretty pictures about my actions. My job is to produce results—so I have to take actions now. Describing what has happened in two different ways still doesn’t change what actually happens, so why do the two perspectives matter?” But here’s a key insight in systems thinking: How we describe our actions in the world affects the kinds of actions we take in the world. So, let’s reexamine the linear and feedback perspectives. Notice how the feedback view draws your attention to the interrelationships among all the events, whereas in the linear view, you are probably drawn to each cause-and-effect event pair. By becoming aware of all the interrelationships involved in a problem, you’re in a much better position to address the problem than if you only saw separate causeand-effect pairs.

The point here isn’t to “wax philosophical” about the intrinsic merits of two perspectives, but to identify one that will help us understand the behavior of complex systems so that we can better manage those systems. The main problem with the linear view is that although it may be a technically accurate way of describing what happened when, it provides very little insight into how things happened and why. The primary purpose of the feedback view, on the other hand, is to gain a better understanding of all the forces that are producing the behaviors we are experiencing.